So, kids, it’s finally coming to this! I’ve been thinking about launching this particular marathon (so to speak) for some time now, and I’ve got my excuse: To celebrate both his newest film release at the end of May and my decades-long love for him, I’m gonna take yinz on a full guided tour of the Godzilla franchise! I know, I know, you’re all very excited, so am I. We’re gonna be working our way through the series from its inception in 1954, all the way through the various “eras” or “periods”, through to our very own 2020, covering all of the films in the canon – and maybe one or two that might stand out as odd additions. We’ve got a ways to cover, so let’s get started, shall we?

Godzilla as a film series and a character begins way back in the mid-‘50s. A partner and protégé of Kurasawa by the name of Honda Ishiro developed the concept of a dark and moody film that presented the lingering horrors of the nuclear attacks his country suffered nearly a decade prior – as well as the immediate fears of nuclear power and proliferation – in the form of a metaphorical manifestation of a giant, atomically-affected monster. Combining his efforts with those of producer Tanaka Tomoyuki, special effects director Tsubaraya Eiji, and composer Ifukube Akira, Honda was able to forge from his vision Gojira (which would be anglicized soon after as Godzilla).

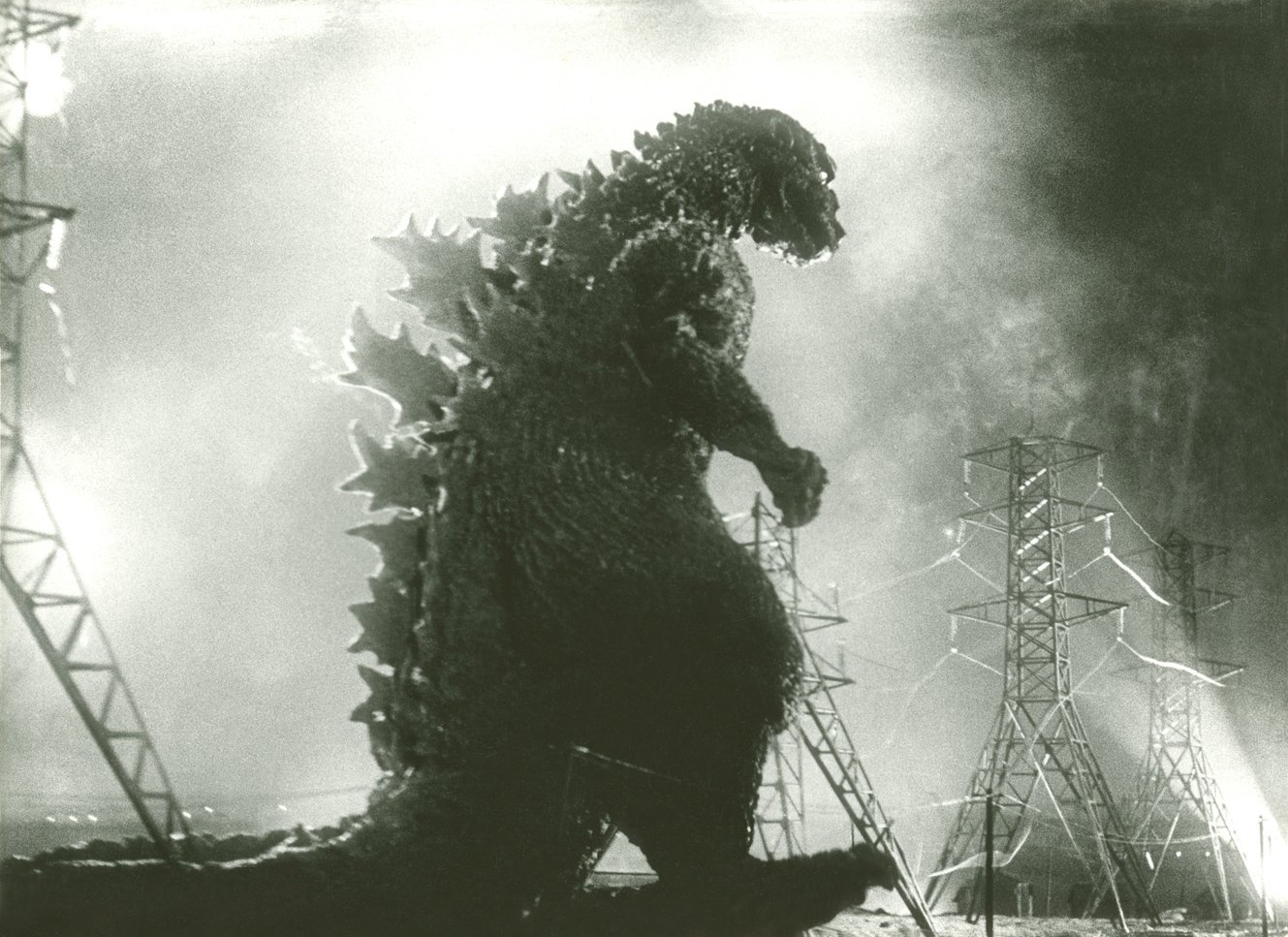

With a name stemming from an amalgam of gorilla and whale, the titular creature is a sort of dinosaurian holdover that’s somehow not only survived in underwater caverns, but also became irradiated due to the nuclear tests being conducted in the Pacific. The subject of legends from Odo Island, Godzilla suddenly makes his deadly presence known to the world, stomping his way through Tokyo, using his immense size and atomic breath to spread death and destruction across the land. The authorities find themselves dumbfounded and unable to stop the creature, until a lone scientist agrees to unleash his new weapon upon the creature – a bomb that essentially disintegrates the oxygen in the affected area, the Oxygen Destroyer (a device that will have ramifications for the series much later down the road) – on the sole condition that it’s never used again.

This film is certainly something else. If you’re watching it for the first time, without any real knowledge of Godzilla at all, the eerie opening credits, complete with Ifukube’s wonderful theme and Godzilla’s trademark roar, would certainly provoke quite a bit of wonder and dread. The pace quickens for a while, speeding through some preambling action before we’re struck by a quick glimpse of the creature’s head over a hill, his roar emanating across the countryside for the first official time. His destruction is presented starkly, gravely, and the civilian casualties are haunting: a mother huddles with her children, awaiting the inevitable, trying to calm the younglings by telling them they’ll be seeing their deceased father soon; children, orphaned and injured, cry and worry as they await treatment at hospitals and makeshift shelters; and the dead litter the streets in the monster’s wake. There’s no real cheese that would characterize future entries, this is straight drama and horror, accented by the massive monster silhouetted against the burning Tokyo skyline. Our hero isn’t some chiseled Roll Fizzlebeef, but rather a desperate and tortured scientist, played in a star-making performance by Hirata Akihiko. Ifukube’s score is nothing short of seminal, often bombastic, always entertaining and mood-setting.

As strong as the film is, it does suffer from its fair share of problems. Much of the ancillary action is dealt with rather quickly, almost amounting to extended montages, giving the overall pacing a rather uneven feel. Though the effects work – the miniatures in particular – was groundbreaking, the effects are inconsistent, both in terms of visuals and sound. Most egregious is the eponymous monster hisself, whose visage alternates rather obviously between the suit (piloted by Nakajima Haruo) and a fairly dodgy puppet, complete with doofy, unblinking eyes. The script has a couple scientific errors (if memory serves, the Mesozoic didn’t extend into the realm of two million years ago, guys), but some of these could very well be a result of the English subtitling (no, I still don’t speak Japanese). The central love triangle also feels a bit unnecessary, but it does admittedly present an opportunity for a more personal connection to the action, having a human anchor that’s not a governmental official.

The sum total, though, is a pure classic for the ages. Though my DVD’s transfer is decidedly dark and scratchy, the film’s power is nonetheless able to pop through the screen, even after decades of technical development and several previous viewings. This is a highly-recommended film, both in and of itself and as a page in the history of film.

Funnily, though, when Toho, the studio that made and currently curates the film and its various sequels, sought to distribute the film abroad, roadblocks unaccounted-for sprang up. American distributors in particular didn’t feel the film would play very well Stateside, what with the foreign language and heavy emphasis on Japanese cultural and historical experience (not to mention the negative implications tossed in the direction of the States, the source of the atomic horrors), and insisted upon re-edited the film to fit their standards. The result wouldn’t see theatres until 1956, and the US was introduced to the Big G in Godzilla: The King of the Monsters.

What American theatre-goers wound up seeing was a highly altered version of Honda’s film. The most glaring difference is the presence of a nigh-constant narration that describes all of what is happening on-screen. Though some of this narration comes from an almost news reel-type narrator, but the majority comes from actor Raymond Burr. Burr plays journalist Steve Martin who is waylaid in Japan thanks to Godzilla’s initial attacks on Japanese ships. Intrigued, Martin strolls through the plot of Gojira, granted immediate access to everyone and everything pertaining to the investigation into the mysterious happenings. As he does, he relates everything to the audience, either through narration or by directly just expositing what he’s seeing. He has personal connections to Emiko, Yamane, and Serizawa, and he always finds himself at the front of any line he wishes to be in.

The major issue with this version of the film is that all of the telling-not-showing stuff detracts from the emotional weight of the film. We don’t experience the events firsthand, alongside the other victims, we’re now voyeurs left to disconnectedly view things from a distance. The Japanese dialogue that hasn’t been hastily dubbed over (in order to make it seem as though Martin truly is as connected and important to the plot as they tell us) is left to run untranslated until some English-speaking character sums it up for us. This erstwhile very Japanese film experience has been turned into an outsider’s view thereof, an entry in a tourist’s guidebook. Martin is our powerful white surrogate, a Forrest Gump who doesn’t so much stumble into epochal events, but rather just effortlessly glides through it all, and we’re the worse off for it.

(And just because it struck me when it was spoken, the English-dubbed Yamane refers to the trilobite he finds in Godzilla’s footprint as a “three-winged worm”. The hell?)

Though a decidedly lesser film, there’s still the raw impact of Godzilla pushing through, and if you’re previously unaware of Gojira, it’s a decent-enough B-style monster flick. But the second you learn of the Japanese version, this one loses nearly all of its weight. Nonetheless, the world is now aware of the Big G, and his exploits will only gain in popularity over the course of the following decades. Things take a bit of a step back, though, with our next subject, Godzilla Raids Again. See yinz tomorrow.