A bitterly cold December afternoon is as good excuse as any for a double feature, especially when you’ve got some good company. After the languid sequel-ness of Pitch Perfect 3, I was looking forward to some actual substance. Howzabout some Aaron Sorkin and some Ridley Scott, eh?

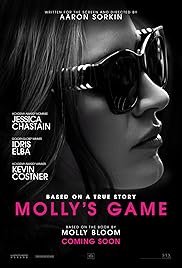

The double-header started off with Sorkin’s directorial debut, Molly’s Game. We follow Molly Bloom (no, not the Ulysses character, but, because this is a Sorkin joint, you’d better believe that one gets mentioned) as she goes from young nigh-Olympic-level skier to the high class pit boss of private poker games. Along the way she gets a heavy coat of jade, strikes it rich, dances with drugs, and runs afoul of the law’s version of a Reed Richards reach-around. Thankfully, she’s got a good lawyer.

Our next bit of true story heaviness was All the Money in the World. And, dammit, ever since it was put into my head, I can’t shake it, so now I’m gonna ruin it for you, too: Whenever I hear the title to this picture, it becomes sung to the tune of “Every Woman in the World” by Air Supply. I’m not sorry, just happy to have some commiserative company.

The story centers on the kidnapping of J.P. Getty III, grandson of the infamously wealthy tycoon, back in 1973. He’s nabbed by factions of the Italian mob with full knowledge of his family’s obscene wealth. Thing is, Old Man Getty’s a notorious skinflint, and he’s not too keen on parting with millions, especially when it involves going through is estranged former daughter-in-law. Thankfully for her, Getty’s bag man Fletcher is on the case.

After each feature, I posed the question: “What did you think?” The answer following Molly was decidedly positive; the one following Money was, shall we say, a bit less decisive. And I knew pretty easily what the issue was.

It wasn’t the acting: M’Lady Jessica Chastain shines once again as Ms. Bloom, complete with some hardcore Sorkin narration throughout. She was even the real Molly Bloom’s immediate choice to portray her. I can easily see some hardware coming her way very soon. Idris Elba provides the solid support you’d expect from him as Molly’s lawyer, and Kevin Costner, though not really in much of the film, shows why he was once one of the most bankable stars in the industry. On the other side, Michelle Williams shows that Manchester by the Sea wasn’t an apex but rather a mission statement of quality, really leaning into her role as the mother of a kidnapped teen. Meanwhile, Christopher Plummer is more than capable of grinching and scrooging things up as a wealthy old miser, and Romain Duris surprises a bit with an actually convincing turn as a kidnapper who reveals something of a soft side as things progress.

It wasn’t the directing: Sure, it was Sorkin’s first directorial rodeo, but it wasn’t all that apparent. Molly’s Game may not be the flashiest or most stylistic debut out there, but it is clear that Sorkin’s learned some things from industry contemporaries over the years. Hell, he even got some occasional advice from David Fincher during filming, and, uh, he kinda knows what he’s doing, so Aaron’s got that going for him. If nothing else, this film should provide him with some deep confidence and experience for future successes. Meanwhile, Ridley Scott sure as hell ain’t no ingenue and he shows it here. Rather than phoning it in like some recent outings (I’m lookin’ at you, Prometheus, The Counselor, Alien: Covenant, and Exodus: Gods and Kings), Scott shows his abilities here with that same hard-hitting style that made Black Hawk Down and even parts of Gladiator and Body of Lies so visceral and tense. Each shot looks great (some side props to DP Dariusz Wolski), and you can feel the tension from the visuals. Which is definitely a plus here, because…

It was the writing. Very much so.

Sorkin may be new to the director’s chair, but he’s a seasoned screenwriter. And then some. I mean, you don’t just start your career with A Few Good Men without some actual talent/aptitude, right? Add to that debut some stellar work on The West Wing, SportsNight, The Social Network, Moneyball, and Steve Jobs, and you’ve got one hell of a resume. He’s got a gift for dialogue, particularly the ability to somehow make some otherwise clunky and unrealistic lines come through appropriately and smoothly, regardless of the actor mouthing them. It certainly helps to have some talented actors, and Chastain shows how much oomph such talent can provide, but it’s not quite necessary. It’s all about timing and flow, timing and flow. Things just flow about like they would in real life, despite the obvious staging, hence his characteristic “walk-and-talk” style: Other writers wouldn’t be able to pull off such scenes, as their words just don’t have the proper mellifluousness for it to work. Few do. Even when the scene’s physical motion doesn’t match it, the dialogue still flows back and forth between the characters with a healthy amount of spark, sass, style, and intelligence.

The same cannot be said of Money‘s writer, David Scarpa. Scarpa’s resume isn’t nearly as full or as lauded as Sorkin’s, comprising only two other prior films, The Last Castle and the dour remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still. If I’m being honest, I’m probably one of a small handful o’ folks who actually likes The Last Castle, but even I’ll admit that the story is slightly preposterous, the plot jars forward too many times for it to be allowable, and the dialogue oscillates between working and thudding. As for that awful remake, he took a concise story (I hesitate to call it tight, but it certainly leans that way, in spite of its time and genre) and blew it out beyond proportions and made the dialogue more wooden than Keanu’s alien acting.

His weakness is on full display in Money, mostly manifesting itself in poor scripting, poor characterization, and poor pacing. The first two are directly linked, in that many times the characters simply explain their motivations to each other and the audience, often multiple times. Nowhere is this more clear than with Plummer’s elder Getty, who never resists an opportunity to expound on his greed, misanthrope, and love of possessions. He monologues about strategy and philosophy, but rarely does much in the way of actually interacting with other characters. One might take that as being a subtle trait, that he’s so far gone into his own world that he can’t really function in the world, but this falters when other characters do the very same thing. Wahlberg’s Fletcher Chase does it, Duris’s Cinquanta does it, even Williams does it a couple times. It’s like how Fences used long speeches to provide characterization, but without that film’s foundation on the stage as an excuse. This also makes the awkward pacing all the more palpable. Y’see, the film jumps between different times, focusing on the present (well, the ’70s, anyway) but occasionally shooting to different points in the past to further illustrate the characters’ characters. This by itself wouldn’t be an issue, but when the script is so bogged down with repetitive and redundant (…yeah…) exposition, these flashbacks just give less time for us to actually experience anything of value. Events just kinda happen, sometimes with little or truncated reaction, and the end feeling is one of mild disappointment. Worst of all, the way things resolve themselves in the end almost come out of nowhere, with one of the characters pulling a 180 seemingly because of a short tirade from an employee that didn’t say all that much that the first character didn’t already know (and make known to us…many times…). Plummer is a great actor, but even he can’t make such weaknesses ultimately come together with success. In the end, the underlying story is still exciting and entertaining, but the connective tissue is more ineffective and worn thin than Randy Johnson’s knees circa 2007. The result is an experience that feels like something’s missing, even though two-and-a-quarter hours have passed.

I don’t know if I’ve ever seen such a classic case of script disparity among high-profile films like this before. It just goes to show how important a good script can be, even with everything else looking gangbusters. Take notes, kids.

One thought on “Molly’s Game & All the Money in the World”